Society in Ancient Athens..!

The concept of a society is defined as a large community made up of smaller groups which contain individuals, while Social Structure is a label for how the people in a society organize themselves and their groups – as stated in a quote from Anthony Giddens, English sociologist: “[Social structure is] patterns of interaction between individuals and groups…” This pattern permits the society order and regulation between groups and individuals. Stratification, however, is a system in which three factors, defined by German sociologist Max Weber in 1922, are used to categories its people; Power, Class and Status.

How were Athenian citizens divided socially?

Power refers to one’s ability to change society in some way (economically, socially or politically), Class is one’s economic standing in their society, and Status is one’s perspective and prestige in how they are viewed. These components are the gears in Social Stratification, which is most definitely present in the Ancient Athenian’s hierarchy system of Citizens, Metics and Slaves.

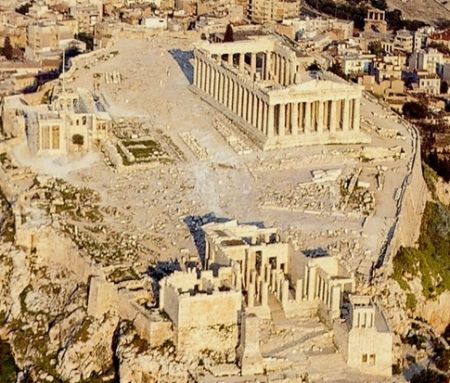

The Stratification of Ancient Athens took the form of a democratic society built into three core classes – Citizens, Metics, and Slaves. Citizen Men took their place at the top of the hierarchical pyramid as the highest class with the most prestige, power, and status. There were three necessary qualities to being a Citizen, claimed by the famous philosopher Aristotle himself: a Citizen must be a man, both of his parents had to be Athenians (a law introduced in 451 BCE) and he had to be registered with his deme (electorate) by age 18.

These restrictions made the Citizen class an elite group, unattainable to many and therefore idolised and desirable – they enjoyed privileges due to their high standings and held the most Power, Class and Status in Ancient Athens. Their perks featured things like political involvement, property and land ownership, and access to social gatherings such as festivals.

Responsibilities.

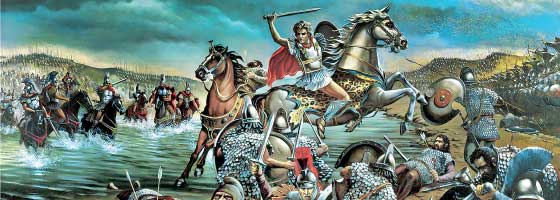

However, they also bore responsibilities to the state, such as their mandatory participance in war from the ages of 18-60, work as a political power such as jury or judge, and personal obligation to protect and feed their households. As yet another example of Athenian social structure, the Citizens stratified themselves in another three class subsections: the Aristoi (Aristocrats) highest of all, the Middle Class and the Thetes. Each subsection could be identified by two qualities – their rankings in the military and how much land they owned.

Aristois often held high positions such as cavalry and navy captains, Middle Class men made up the hoplites (infantry), while Thetes could have important roles in the navy like rowers. As the highest class and an ideal for all Athenians, Citizens had a particular lifestyle to chase and maintain, reflected in this quote from a character in the Citizen philosopher and historian Xenophon’s ‘Economicus’: “I concern myself with ways of getting rich and having a lot of money.”

image source-https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiVsqchIgGjKJv8aWqeUrUf-4EyesVTwXdB6g35guY8-qoTKbVctN_qyYJJ0caSe8rYt29A8JHn-DkF68rMcBm95z2i9-5-zng7pQg45HHik2GQ1iHW8PzOjvy5lgzBviAfQ85QymL1OKBo/s1600/g_map_city_states.jpg

The Metic class.

The Metic class, in stark contradiction, consisted of freed slaves or foreigners wishing to live permanently in Athens. Their requirements specified also being registered in their demes, but they also needed a patron – an Athenian who supported their life in Athens. Both males and females could be Metics. As what is considered the ‘working class’ or business class of Athens, Metics often oversaw labour and entered into business deals with Citizens, who socially saw them as equals, though stratified below them in the hierarchy.

Due to their ability to engage in business, Metics could actually acquire an abundance of wealth, and although still being classified as ‘underneath’ the Citizens, they could be richer than some of them. However, they were also taxed incredibly – including an annual tax called the metoikion which let them stay in Athens – and the wealthier of Metics were encouraged to contribute liturgies (voluntary taxes). As well as taxes, Metic men were expected to serve in an armed force but were not trained, could not vote or hold any political power, or own property.

Metics VS Slaves.

Other benefits to being a Metic included the freedom to worship their own gods, their marriages were legally recognised, the ability to attend festivals and theatre, and Metic men were able to socialise with Citizen men. In very rare cases Metics were able to move from Meticship to Citizenship, an example of social mobility. One such case is the story of Pasion, a slave who was granted Citizenship after being freed and dedicating a large portion of his wealth to the State of Athens.

Slaves were (usually) non-Greeks servants who could originate from places such as Modern-day Syria, Turkey and Bulgaria. Ways of becoming a slave include being kidnapped from their home countries, being born into slavery, or being captured as a prisoner of war. They were legally owned by whoever had bought them, and held the lowest position on the hierarchical pyramid.

The Greeks believed in a concept called Natural Slavery, where the idea of owning another person was not ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ to them, it was simply natural. They prided themselves on being ‘Thinkers’, great mathematicians, philosophers, scientists, inventors etc, so in their mindset, the daily physical labour needed for an individual’s or the state’s maintenance was simply below them, a responsibility belonging to the slaves they claimed – this was a widespread cultural belief among the Athenians.

Slave System

Slaves were bought by auction or general sale, from places like the Agora or the port from which they arrived, and their prices varied according to their age, appearance, attitude and abilities. Their generally high price served as another high-class status for the Citizens of Athens. They were either privately owned (by Citizens or Metics, individuals or families) or state-owned (owned by Athens, working for the government). Privately-owned, domestic slaves overlooked actions such as a groom, butler, cook, nurse, washer, cleaner – all dependent on their individual traits and what their owner assigned them to. State-owned slaves minded jobs including executioners, coin-makers, and clerks. As stated in Xenophon’s ‘Memorabilia’, “Those who can do so buy slaves to share their work with them.”

Another form of work for the domestic slaves of Athens was being hired out by their owners to perform any array of skills for others as entertainment. In similar fashion, another subsection of Slaves existed called the Hetaira. Hetaira were what could be vaguely identified as similar to modern-day prostitutes and were made up mostly of slave – sometimes Metic – women, carefully chosen for mainly their looks and also any preliminary talents. Women of the Hetaira were trained to specialise in certain entertainment skills and educated in various topics, including philosophy and politics, subjects of which women were otherwise strictly banned from. Unlike typical prostitution, the Hetaira’s objectives were to provide female company to men attending symposia (dinner parties), which primarily featured holding intelligent conversation with their clients.

Hetaira possessed what could be regarded as a fair amount of freedom in their positions. They were paid for their services, protected as state property, and were not held to the same esteems as high-class women of Athens, meaning they could go where they wanted when they wanted.

The relationship between the Citizens and Slaves of Ancient Athens was a complex and context-dependent situation that presented its class members with an array of benefits and negatives based on a variety of factors.

https://massaget.kz/userdata/uploads/u18/5416545.JPG

Life of a Slave.

Negatives of being a slave featured punishments (often whippings or beatings), barely ever extreme, slaves working in mines usually suffered early deaths due to the dangerous conditions of their work (an example of some slaves who had no relationship with those they worked for), slave marriages were not recognised by the state and could be separated at will, and slaves were assigned specific names only used for slaves once claimed by their owners.

Otherwise, the average domestic slave privately owned by a Citizen or Metic was generally treated far better than non-domestic slaves or slaves of other states in Greece – this was due to the cultural belief that Athenians should be composed and in control of themselves, therefore acts of cruelty etc were seen as barbaric. Other states often found this relationship to be unusual, reflected in this quote by Xenophon, ‘Constitution of Athens’: “Some people are also surprised that the Athenians allow their slaves to live in the lap of luxury and some of them indeed to live a life of real magnificence, but in this respect too I consider that they have reasons on their side.”

Of course, slaves were still punished, but more ‘fairly’ in comparison to those of other polis (city-states). Benefits of the domestic relationship between Citizens and Slaves for different households included the ability to back-talk to their owners (to a certain degree), to be able to dress in normal clothes, to practice their own religion, to be treated almost like a family member in some instances, and to be executed only by trial, not by their owner of his own volition. These offer evidence towards how differential the lives of slaves and Citizens could be, entirely dependent on each other.

Day-to-Day Chores.

Slaves carried out important maintenance and day-to-today activities that Citizens needed to be done, but believed was a waste of time. Without slaves, Citizens would not be able to focus on politics and the pursuit of knowledge, which Athenians are ultimately known for. Slaves relied on Citizens as a means of living – food, shelter, sometimes money, work.

They carried out the menial business, overseen by their masters, and conditional on several qualities (age, ability, attitude), could be treated well (considering the circumstances). Therefore, slaves relied on Citizens. A ‘strange’ example of a relationship between Citizens and Slaves is the Hetaira. The women of the Hetaira were prized for their discussion and intelligence above anything else, welcomed into the company and entertainment of Citizen and Metic men.

Though still serving them in a transactional manner – the men gained companionship, while the women were often paid for their service – the mingling of the highest and lowest classes is somewhat unusual.

Slave-Citizen Relationships

Arguably, the greatest benefit of a slave’s relationships with the Citizens of Athens would be the possibility of Manumission – undergoing the process of being granted freedom by their owner or the state. Manumission is a form of social mobility amongst the Athenians which allowed for slaves to leave their assigned class in a range of ways: buying their own freedom, being gifted their freedom and an owner granting them freedom in his will.

These concepts support the idea that some relationships of Slave and Master in Ancient Athens could have been positively based, benefiting both parties. In the story of the slave Pasion, Manumission was granted after his owners left their bank to him after death due to his exemplary work. Being able to pay for freedom, Pasion became a Metic, but instead of leaving Greece or living out life as a Metic, Pasion donated money towards weaponry for the Athenian Army – which led to the State of Athens deciding he deserved to become a Citizen for his efforts.

Despite being born a slave and naturally unqualified for the Citizenship position, other Citizens deemed him worthy based on his actions.Their relationship could hold a close physical proximity, as domestic slaves often lived with their owners and could be considered a member of the household – and Citizen men were responsible for their protection – leading to another complicated assortment of outcomes regarding how they interacted with one another.

Slaves in the Family

Slaves could be treated like a family member (included in family rituals), they could be assigned to escort young sons of Citizens to, during and from school and even punish them for not paying attention in class or the wives of Citizens, who were unable to walk the streets of Athens without a male chaperone. Again here we see how useful and indispensable slaves proved to be to their masters, making it desirable to keep them safe, reflected in this quote by Xenophon from ‘Memorabilia’: “things that are both acquired and looked after with care.” The multifaceted nature of Slave and Citizen relationships is difficult to define, due to the numerous variables that played into it.

https://healthy-food-near-me.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/15-top-rated-day-trips-from-athens-2.webp

The identities of Slaves and Citizens were largely, if not entirely, based on their social stratification of the system they lived in. Slaves, as an identity, were property owned by someone rather than a person of their own right – this played into the kinds of behaviour and expectations they were held to throughout their lives. Citizens in their own respect were the privileged class, a title reserved for the most esteemed of Athenians.

Stratification dictated the ways in which they interacted with one another, their classes’ transactional nature directly feeding into their positions (Citizens stayed rich or respected while Slaves stayed poor or overlooked). Behaviorally, Citizens relied on their stratified identities to function in their society. Whilst stratified into the Citizen class, they were further stratified into Aristoi, Middle Class and Thetes. Their identities as the ‘highest class’ is dependent on the existence of the lower classes, or more pointedly, the slave class.

Treatment Ideals.

Although the treatment of each slave was almost entirely up to the owner, they were generally treated well due to how expensive they were – even though slaves were looked down upon, they were still a prized possession of the Citizens, which was an important aspect of their relationships.

Another example of this could be the protection of slaves from public discrimination or violence by the fact that they wear the same clothing as any other man: “If the law permitted a free man to strike a slave or a metic or a freedman, he would often find that he had mistaken an Athenian for a slave and struck him, for, so far as clothing and general appearance are concerned, the common people look just the same as the slaves and metics,” (Xenophon in Constitution of Athens’).

image source-https://goldenmariner.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Golden-Age-Athens-2.jpg

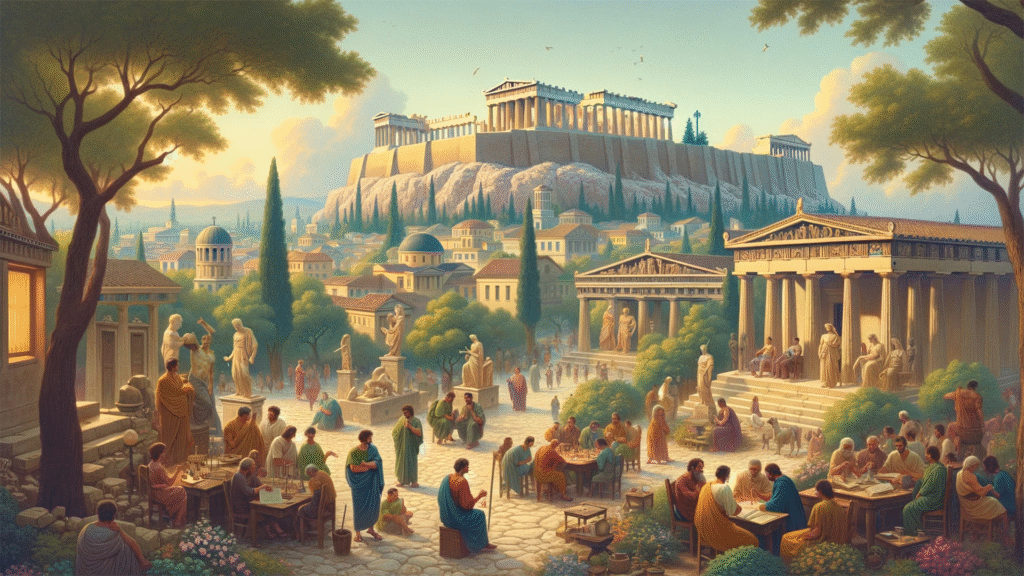

Metics and Citizens held what could be identified as a considerably friendly relationship. Socially, Citizens had accepted Metic men as equals to them, inviting them to symposia, social gatherings in gymnasia, and procuring business deals with them, which – compared to the generalised treatment of the slave class, could be considered honours. Work was something that could bond the two classes closely, as Metics were often the men who oversaw Citizen businesses, and therefore kept close connection to in one way or another, sealed by mutual trust or respect.

Social Mobility.

Mobility between Citizenship and Meticship was incredibly tight, as Metics were freed slaves or foreigners which usually disqualified them from the running – aside from rare cases, such as the slave-born citizen Pasion, a man who rose through the Athens hierarchy based on his hard work at his owners’ bank and then further acts of devotion to the polis by donating equipment to the army, allowing him to go from Slave to Metic to Citizen – but in a rather unusual sense it seemed as though the Citizens did not mind this about the Metic men.

Citizens benefited from the taxes Metics were put through, their money contributing to the State and individual properties (even though Metics were not allowed to own property), especially since Metics could often become quite wealthy – some richer than lower-class Citizens. Metics were also only able to stay in Athens due to a Citizen sponsor, meaning every Metic that lived in Athens had a Citizen to vouch for their presence, and to be registered in their deme (electorate) – so in exchange for their work and provisions to the economy of Athens, Citizens welcomed the Metics socially, legally, and semi-politically.

Identities.

Pasion’s life works as an example of a model Metic-Citizen relationship – though (mostly) formally restricted from one another, the Citizens and the Metics often respected and accepted each other for the effort their classes contributed to the system, and in his case, could be rewarded for such if deserved.

In a stratified society, identities are often if not always majorly impacted by the classes an individual is placed in. For Metics and Citizens, their relationship as equal company and partners in business was readily influenced by their class statuses and the behaviour that came of them. Considering the responsibilities of a Metic due to their class, their identity could be bound to the work they fulfilled for a Citizen and vice versa.

Athenian Minds.

They behaved cordially due to both groups holding higher classes than the other majority – a kind of allyship between the empowered classes. Due to the fact some Metics could be wealthier than some Citizens, they could be held to a similar esteem as other high-end Citizens. Lysias was a famous Metic and speech writer who wrote about an old Athenian debate: “good metic/bad citizen”.

It was apparent that Athenians believed that, for the polis, a good metic was better than a bad citizen, which proves that the identity labels of these groups barely mattered to the Athenians – it was their behaviour that made any kind of withstanding reputation amongst them. What they could offer the people, based on the responsibilities held by their individual classes (politics and intelligence for the Citizens, economy and business for the Metics) held almost all the weight of a respected being in Athens.

Fulfilling their role in the system is what Metics and Citizens craved, upholding their identities expected of them, and their relationship with one another was a key aspect of it. Truly, the identity of an Ancient Athenian was largely shaped by the stratification of their society.

One Comment